In the begining, there was only binary data.

Then Netscape said, let there be javascript.

But Javascript didn’t play nice with binary data.

And that is the genesis of this post.

Any serious server side language must play nice with binary data. Node’s strategy was to introduce Buffers. If you have dealt with streams or crypto in node.js, chances are you have dealt with Buffers. This one is about one such encounter.

One fine afternoon we were trying to generate random codes. Each code is just a random string of ascii characters (like P4AZHEDXWA). There was just one problem, we were trying to generate 200 million unique codes, and we ran into a problem with Buffers.

When marketing comes to us with gigantic promotional campaigns (like this one that requires doling out 200 million unique promo codes), sometimes things get pushed to their limits. In the process, we discover a thing or two about the tools we use everyday. That’s the beauty of scale.

But first, let me describe how we decided to generate these codes.

Step 1: Get a good deal of entropy.

This one was easy, /dev/random was enough. We estimated we would need a couple of gigs of random data, hence this

dd if=/dev/random of=random.data bs=1k count=2048000

This was quite fast on my Mac, barely taking a couple of minutes.

Step 2: Read n bytes at a time, check for uniqueness, and generate

In this step, we would read a chunk of bytes from the random seed, check if that chunk is unique (hasn’t been seen yet), and BASE32 encode it to get our promo code.

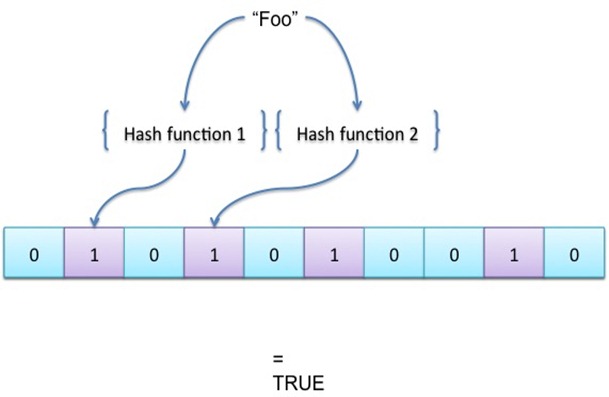

How to you check uniqueness of such a large set? Our approach involved using Bloom filters, which are essentially a set of hashes used to set bits in a buffer.

That is potentially the worst description of bloom filters one can come up with, but Bloom filters are such a nice data structure that we use them often and I would probably cover them in an independent post.

Back to the excercise, we fire up the program and generate the codes. The curious thing we noticed was that the nodejs script that was generating the codes went very fast in the begining, and then kept getting slower and slower. Eventaully, at around 6 million codes, it would just seem to hang.

Now one of the nice things about bloom is that adding to a bloom filter (or looking up from it) is a constant time operation. We had already generated all the randomness we needed and dumped it to a file, so the script couldn’t potentially be waiting for entropy. strace offered the first clue - we found that the script kept asking for more and more memory, and at around 6 Million codes, having exhausted all the system memory, it just seemed to hang.

After a bit of debugging and some crazy insights, we were able to isolate the problem to BitBuffers, a class used in the implementation of Bloom Filters we used.

It all boiled down to this

set: function(index, bool) {

if(bool) {

this.buffer[index >> 3] |= 1 << (index % 8)

} else {

this.buffer[index >> 3] &= ~(1 << (index % 8))

}

}I can imagine the Crockford fans jump in joyous exhilaration with a look of ‘I told you so’. Yes, its a bad idea to use bitshifts to do a divide by 8, even if its performant. But first, an explanation of what was causing the leak is in order.

Each input chunk (that is being checked for uniqueness) is converted into a set of hashes (using FNV). Each hash code is then used to set a bit position in a buffer. To calculate the bit position, the hash is divided by 8.

Its here that this fails. If the hash value is too big (and the sign bit is set), the following will not be equivalent

index >> 3 != index/8Want to see it for yourself? Try with 2415919103 (which is 0x8fffffff). You will get a negative number when you do a bitshift using ».

Did you even know there is a Zero Fill Right Shift operator in javascript (>>>). Which is different from the sign propogating right shift operator (») and was exactly meant for cases like this. Now this may be a WTFJS moment for quite a few of us, but changing to the right operator fixed this issue.

But that’s not the end of it. Don’t you need to know how negative array index lead to memory leak of this sort? That’s where the Buffer class comes in. You see, in the sample code above, this.buffer is an instance of Buffer, which is not an instance of Array. Don’t take my word for it, try it out yourself.

> var x= new Buffer(8)

undefined

> x instanceof Array

false

> x[4] = 12

12

> x

<Buffer 00 20 00 00 0c 00 00 30>So how is array indexing working on the Buffer, when there is no way to overload operators in javascript.

The for loop comes to our rescue

> for (var k in x) { console.log(k) };

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

length

parent

offset

...

...In javascript, the Array Index Operator can also be used to access a member property. E.g. you could do x[‘length’] instead of x.length. Now let’s see what happens when we try an index that is out of bound?

x[-1] = 4

> x[-1] = 4

4

> x[-20] = 4

4

> for (var k in x) { console.log(k) };

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

length

parent

offset

-1

-20

...

...So there we have it. If you perform an out of bounds indexing on a Buffer, that becomes a property of the Buffer.You may end up with a gigantic memory leak if you aren’t careful about maintaining the bounds yourself.

BTW, we are hiring, and if this sort of workdebugging excites you, write to me at qasim at paytm dot com.