We recently switched our infrastructure on Amazon Web Services to use auto scaling. Scaling capacity up and down, based on certain conditions (e.g. traffic) is cool by itself, but site cost efficiency and better capacity planning are the oft cited reasons for autoscaling (in case you go pitch this to management after reading this). The icing on the cake is that it makes your overall infrastructure much more robust and fault tolerant. That’s because

You can’t autoscale what You can’t automate. - Yogi Berra

I just made that quote up, but the idea is sound. Let me explain. When most people move their infra to EC2, they setup things by hand. So you would start with a certain capacity, which would be good enough to handle your peak load, and some more, planning for that future growth. (What a waste though, most ecommerce websites will have a near zero traffic between 2-6 AM, and peak and average load differ by a good margin). Then if you are lucky enough you would have a scaling problem at hand. Or myopic enough to have started with an stingy budget in the first place. Anyhow you would be adding a second server. That’s assuming most app stacks will scale horizontally. In case yours won’t, you would upgrade your existing one to a higher capacity.

In either case, you would realize that there are quite a few things to do when setting up that new server, from TCP tuning to system hardening to tools installation that you probably didn’t bother to capture, and it takes longer than expected and not everything is in your head and has to be rediscovered. Even if you did make an AMI out of the first server, there will be surprises as long as there is a decent amount of time lapse. Try doing a mock server replacement drill and you would know what I mean.

Autoscale changes that. Your servers will be brought up and down every day, and that is better than any number of mock drills you could run planning for that disaster situation. It forces you to define every detail, and to do it well, because a new server should be up and running within a few minutes.

This is the first part of my series on autoscaling - what you need to think about when deciding to autoscale. Our tech stack consists of node.js, GO, python, redis, mariadb and nginx (and kafka and hadoop, and … - did I miss anything cool out there?), but its only the app servers that we autoscale, not the DB. Here is what we did.

Deployment

This word takes a different meaning altogather when you autoscale. Earlier, you would deploy to instances (eg cap-deploy to adsrv-01). Now, the instances would deploy code themselves. Because what servers are running and how many are running is a number that keeps changing. So before we talk deployments, lets talk provisioning.

Provisioning

Prior to autoscaling, there was no provisioning. We had set things up manually, starting with a base image to which we would add all the software. Then via a git based deployment, we would deploy code. Then we would configure stuff like nginx, often manually. Sounds pathetic, but thats how most cloud companies would do it. At the end of it, we would create an image, so we are better off next time.

With autoscale, this simply won’t work. The first major change we did was to move from EBS stores to instance stores.

Using Instance stores

EBS on EC2 is persistent. Instance storage is ephermal. That makes most people go for EBS. After all, you want your data to be there even after you reboot. What we don’t realize is that EBS is so much more expensive than instance store, and Instance stores are more performant. Citation needed.

For example, if you are running redis, and if you are storing session data in redis, in a lot of cases you would get away by storing the redis on disk DB on instance store. Redis dumps data very frequently to disk, and it could be as fast as once a minute or once every 15 minutes if you haven’t changed the defaults depending on how many visitors you have. Now that’s a lot of IO, and it doesn’t make much sense to pay for it, does it?

That apart, when you bring servers up and down several times a day, you simply can’t use EBS for anything but the root partition. Okay, if you store your logs on EBS, when the instance is terminated, the EBS volume would either go away depending on your termination policy, or you are going to be left with lots and lots of Idle volumes. Neither is a good scenario.

So in your autoscale config, you would want to identify what logs you need to persist, and persist them somewhere else. S3 is a very reasonable choice, though you may even use NFS. Your apps no longer write to EBS - they write to the instance store, and X minutes or so you sync up the logs. This is for things like nginx logs, where you can manage losing some of them. If any of your logs are more critical than that, you shouldn’t be writing them to filesystem in the first place. (You should be writing to a logging server, or some remote data store that is on persistent storage).

But its not just the logs that go on the instance store. Code is Ephermal too, and your code should be on instance store as well. It should be pretty obvious by now that even if you burn the code on AMI, well, how are you going to update it to the latest revision when a new instance comes up. I recommend that your AMI volumes have none of your code, only the stack. For example, our AMI images are only linux+nginx+node.js, and do not contain any code at all. Code is provisioned via user data scripts.

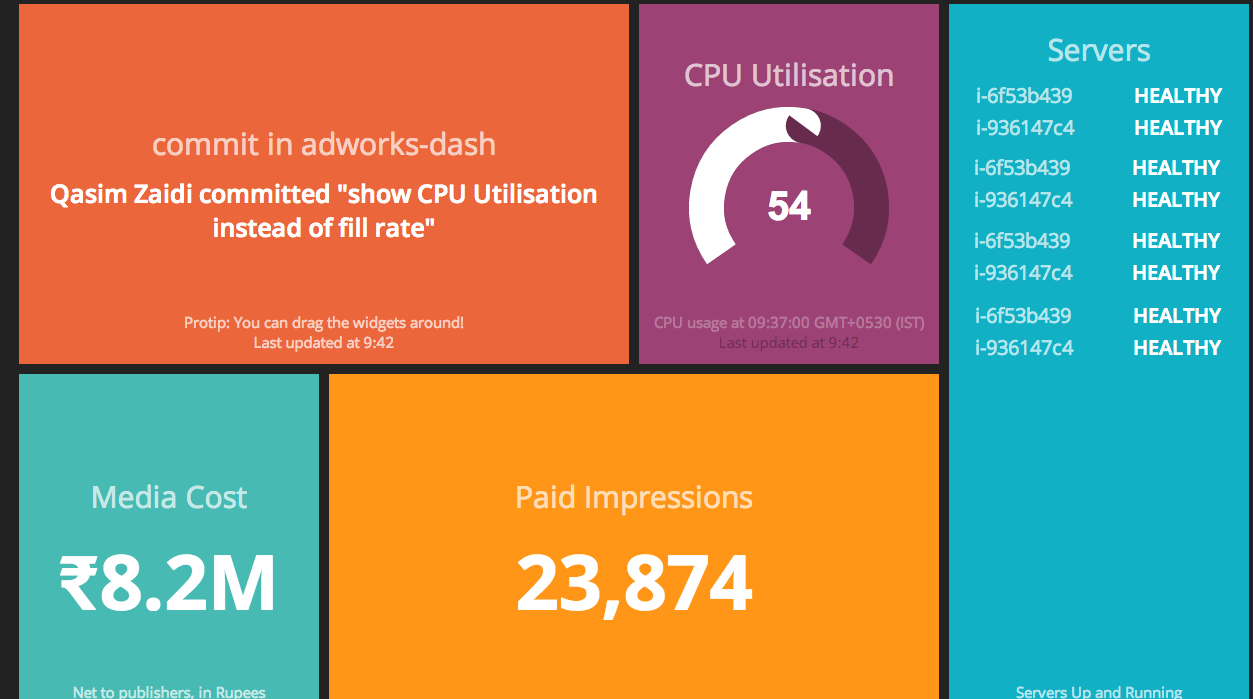

I guess that’s it for the part 1. I leave you with a shot of our dashing developer dashboard - which is primarily there to show me how many instances are up and running at any time. The numbers have been fudged deliberately, don’t try to read too much into them.

Update : Part 2 of this series is now available.